What happens when you remove job titles and hierarchy altogether? For Simon Dixon, CEO of Hatmill – the No. 1 UK's Best Workplace (Medium) – it’s clarity. Find out how self-management and radical trust has created a culture free from internal competition, helping this employee-owned consultancy to develop high-trust leadership while everyone leads.

Your employees frequently mention your Teal management structure as a key aspect of why the feel Hatmill is such a fantastic workplace. Can you tell us about this?

Simon: We've been employee-owned for four years, and we are a self-managing organisation, meaning we don't have any hierarchy. There are no job titles. No one's got a boss (although they'll probably say I am the boss, but it doesn't really quite work like that).

When you haven't got the classic pyramid in terms of your organisational structure, what you get is a level of fluidity which enables members of the team to step in and out of leadership roles when they've got something to add; then step back when they feel they don't. It probably takes 18 months to two years for someone joining Hatmill to figure out how it works because we don't really have a policy of telling people how self-management works. It's a learning journey that they have to go on.

For supply chain projects without a designated leader, how can you balance making urgent, critical decisions while maintaining a high-trust environment when there's conflict?

Simon: Although we are non-hierarchical as an organisation, when we have a project we do designate a leader. The team will come together as they form a team, and they will decide who is going to be the leader on that project. There is a designated leader primarily because if we're working with a client, they would like to know who the person is who's principally responsible for that programme. However, it's not necessarily always the person you think it might be – depending on the shape of the project, who the client is, who has the relationships, and the nature of the challenge all goes into it.

We tend to find that because the leader has been selected from within the team, that 'leader' tends to have the support of the team more so than a hierarchically designated individual. Other critical decisions are made in the same way as any other team would make on that basis.

What does high-trust leadership mean to you?

Simon: I think to develop the culture of high trust, it has to permeate every single thing that you do. Some organisations will talk about having high levels of trust. If they do that, I would ask to see their expenses policy, because I think it goes down to that level. If you need an expenses policy, can you really argue that you've got high levels of trust with your team, rather than just saying, 'Well, actually, just spend what you think is appropriate for the task that we're asking you to do'? At the core of that is treating people like adults. Of course, I appreciate some leaders operate in a regulated environment and there needs to be guidance aligned with that. But I also think that there's a valid point of questioning, in addition to the regulatory requirements, how many additional rules you really need to put on people in terms of boundaries?

Taking it down to that sort of minute, basic level demonstrates if you really trust the team or not. At Hatmill, we have that trust that people will do the right thing.

Covid really drew out that we needed to walk the walk, and so another key tenet of trust is high levels of transparency – allowing everyone in the team to have total visibility of how the business is doing, whether we're in danger of making redundancies or whatever. Every interaction builds or erodes trust, and doing some key things like that when the chips are down, massively adds to the trust.

What sort of mindful practices or habits do you have that help send out the message of high-trust when people are leading in your organisation?

Simon: We have weekly written communication where everyone who's on a project provides a summary of how their project is going – and 'good', 'bad', or 'indifferent', which is a message for me in terms of some of the things I'm seeing and things that we need to focus on, or calling out something that's gone well the previous week so that we celebrate success.

Twice a year, we get together off-site for a three-day event, both in June and December, where we get to make connections, welcome new people into the team, share more detail around projects we've been working on, and quite a bit of socialising. What we've learned over the years is not to fill that agenda with lots of business content. Leave good spaces for 2–3 hours for people to just go on walks together; let the runners go and do 5k or 10k together; let the cyclists go riding – that sort of thing where people can make those connections. We bring colleagues together with a purpose while creating loads of freedom for them to connect and build relationships in different ways. Ultimately, when they then find themselves working together on a project, they've got that thread of trust that they can then build on from that point of view.

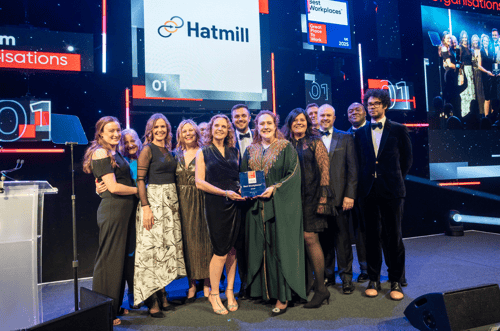

Above: Hatmill receives their trophy at the 2025 UK's Best Workplaces Awards, ranked No. 1 in the Medium size category.

Above: Hatmill receives their trophy at the 2025 UK's Best Workplaces Awards, ranked No. 1 in the Medium size category. How does your non-hierarchical structure play out in your organisation in terms of your leadership?

Simon: That fluidity of leadership allows that at any given point on any given project, someone with the most experience in whatever the challenge is can step up. It's, 'I've probably got more expertise in this than the rest of the team. These are my thoughts'. They're not relying on the director, or the senior manager, or whoever it might be in a conventional organisation, to determine the path.

I've worked in conventional organisations and been part of that, and that was one of the things that drove me to make Hatmill self-managing – because I saw how that way of working can create bottlenecks which didn't necessarily get the best outcomes. At Hatmill, to create that fluidity, everyone can show some leadership from time to time, and everyone has it upon themselves to develop trust in others so that people will trust them to step into and carry out leadership roles effectively.

By removing the pyramid, we've removed the internal competition, and once you remove the internal competition everyone's willing to help each other because their competitive spirit is pointing outside the organisation. We want to be better than our competitors, we don't want to be better than our colleagues.

How do you drive two-way connection between colleagues?

Simon: Because we don't have managers, we needed to find a way to do the things that managers generally do. The core part of that is two-way feedback. For example, if you've been working together on a project with someone, every six months you'd sit down and give each other feedback – both formative and congratulatory/supportive feedback – so people can observe and understand where they can improve as well as what they do well. It's the same for me and everyone else. It's an entirely two-way thing, and always done face-to-face.

We have a structure we use to guide people in terms of the example of the behaviour, the effect it had, to change or continue. It's a nice, simple framework. The answer after receiving feedback is always 'Thank you', and recognising that people are giving you the feedback in order to help you improve, not using it as a weapon.

Critically, we've removed any competition for roles and promotion. So there's nothing to be gained by putting someone down in a way of 'I'm marking you down because I might get the next promotion, I'm better than you.' Once you've removed that competition, it can be done in a genuinely helpful way.

How would you say that you drive a culture of respect in each of your teams?

Simon: It's around genuine interest in the welfare of the individual. Every company would say, 'We really care about our people.' I would respond with: 'Great! So what do you do when the chips are down? What do you do when someone has a bereavement leave and they need a bit longer than the standard bereavement leave policy will allow? Do you say, 'Well, actually, you get a week and a half, and that's it?' Or, 'Yeah, find whatever you need' and adapt to those situations?

Similarly with mistakes: It's almost conventional thinking when someone makes a mistake, to build a rule or a policy to ensure it never happens again. And before you know it, they all build up and you've got 14 ring binders full of policies that no one could possibly carry in their head to remember what they're meant to do or not to do. The brave thing to do at that point is to go: Okay, you made a mistake. Let's help the individual. Let's maybe share that as a story, because it's the stories that permeate through organisations that create a bit of folklore about what happened and how we deal with that rather than a policy.

We learn from that as an organisation, moving forward and resisting drifting to convention. Still trust people and still treat them like adults, making sure that that happens no matter what comes along.

How do you keep your people focused on how they show up to maintain trust in tough times?

Simon: It's about transparency – if people are clear on where you are and where you're trying to get to, then there are no surprises. If there are no surprises, you don't get any knee-jerk reactions in behaviours. We don't get too high with the wins or too low with the losses; rather maintaining a steady level of transparency and clarity over how things are going, and we tend to get better results like that.

How do you measure progress in driving high-trust leadership or culture more formally?

Simon: The Great Place to Work survey is our measure – and we treat the survey in two ways: One, it's a really useful measure. Two, I encourage employees that if they think there is something that we should be doing better, do not wait for the survey. Just get involved and fix it. Bring it to someone's attention, and do something about it.

One of the fears I had when we started with Great Place To Work four years ago was that it would push that sort of feedback mechanism underground, which was never the intention. There's a real benefit to confidentiality around doing the survey. At the same time, we need our people to feel free to step forward and say if there's something we can do better, and for them to grab it and go for it, fix it now.

Is a self-managed, non-hierarchical structure really possible for larger organisations?

Simon: There's a great book by Frederic Laloux called Reinventing Organisations, which talks around self-managing non-hierarchical companies. He's dealt with businesses with thousands of employees who work in a self-managing way, so that's a great reference text.

But ultimately, I think it's around spotting the cliques, the politics that start to emerge, and ensuring the team closes that down pretty quickly. It's this sort of stuff that undermines all organisations. It's about making sure you've got that single team focus that everyone's pulling in the same direction.

What do you think helps leaders become more self-aware of how their behaviours impact trust within their teams?

Simon: We use our feedback process for exactly that. The thing I've seen in the corporate world, before I was in Hatmill, was 360 feedback but only occasionally done. At Hatmill, we've done this every six months or more frequently. It is the normal way of doing feedback for us. And because we've not got that manager/subordinate structure, that dynamic changes depending on what project you've been working on and who you've been working with. But people understand that the feedback they get is from colleagues who are effectively at the same level, and it tends to be far more powerful than when you get feedback from a manager.

When you're getting 360 feedback from all your colleagues whom you work with, it becomes very honest and very helpful if you've got the right culture.

How does remuneration work in a flat structured organisation? Presumably transparency is key. Is it role-based or competency based?

Simon: It is a challenge, it's not straightforward. Ultimately, you need to pay a market rate to attract someone to come and work with you. And when you're hiring people from graduate level through to someone who's got 30 or 40 years of industry experience, you clearly don't pay them all the same amount of money because it just wouldn't work. It's something that we've shared with the team. When we asked, 'Do you want pay to be entirely transparent across the team? Do you all want to know what each other earns?' The feedback we got from the team was, 'No, we don't. We want that to be kept confidential'. I thought this was really interesting! We didn't delve into it particularly deeply, but it was overwhelmingly a 'No, thank you.'

Usually, the way that pay increases over a period is typically: if you're in an organisation, you would get a leap up a step when you got promoted to your next level. But imagine that there is a chart of pay versus time, and we've placed a curve through those steps. If you get really good feedback scores from your colleagues, the amount of the overall salary pot increases and you move faster up that curve than someone who's getting worse feedback scores. So individuals still get the salary progression through a sort of parabolic curve that flattens at the top end of your management consultancy wages.

We do have a lot of debate around whether feedback should play into salary because some people are nervous about giving poor scores, even when performance has been poor, because they don't want to detrimentally affect someone's pay. It's an imperfect world, but I believe that, for us at least, it works better than the convention.

What single most important piece of advice would you give leaders to help drive high-trust leadership in their organisation?

Simon: I'd focus on what's currently stopping people from building high-trust relationships with everyone they work with. Maybe it's the fear of doing something unconventional. We all know how to build trusted relationships outside of work. So to think that we suddenly lose that ability when we step through the doors of our workplace is slightly weird to me. Just behave like a good human and do what you would do outside of work, even though you have a uniform on or whatever it is that you step into when you go to work.

We don't necessarily need to create a mechanism or a framework for it. Just go and do what you do when you've built trust with other people outside of work.